Link to a Word Document with a Module Template Creation Guide.

When you design your course, we recommend that your content be “chunked” into discrete, manageable units of learning. Whatever you decide to call it – a module, session, unit, or section, the most important thing to remember is to present materials to your students in a meaningful and helpful way. Treat it as a “learning guide” to help students make connections with what they are studying to their future endeavors by writing narrative pieces that include important and worthwhile instructions/ references.

One way to do this is to follow a weekly format that aims for each weeks’ layout to be similar, and predictable. A recommended format for a week is to provide the following:

Teaching Notes

This is a private section to leave notes for yourself (or other instructors) to guide you through facilitating the specific week. It can range from reminders to make a special announcement for an assignment that is outside a regularly scheduled deadline to a script with PPT slides to make a needed video or lecture presentation. While this section will not be seen by the students, we consider it important to include this section to help you keep track of facilitating notes and potential pitfalls to avoid.

Overview

The Overview section begins with a 1-2 short paragraph narrative, which provides the context or “glue” for the module’s content and learning activities. Speak directly to the students and include information that frames the content in your voice and with your perspective on the content. Include any critical information that may have been traditionally delivered orally in the face-to-face classroom. This might include illustrative stories or examples, challenges students may encounter with key concepts, typical misconceptions, an overview of the module’s activities, and so on. If this section becomes too lengthy, you might also elect to include specific portions within the context of the rest of the module sections.

Weekly Learning Outcomes/Objectives

Unit-level objectives that describe what students should be able to do by the end of this specific week.

After completion of this week’s activities, you should be able to:

- Identify….

- Analyze…

- Please refer to the Bloom’s taxonomy list for other learning verbs.

These weekly objectives should draw a clear connecting line to the overall course learning outcomes.

Required (& Recommended) Readings and Resources

Elaborate on the information provided in the Syllabus by explaining why, how, and in what order students should work through the resource materials. For example, if you include a YouTube video as a course resource, briefly explain your rationale for selecting that particular video, information students should pay close attention, etc.

Instructional Materials

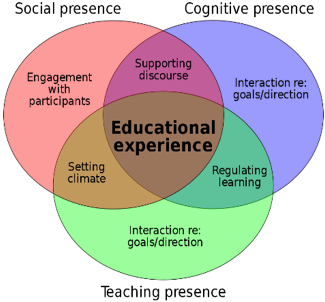

This section can be excluded if all your instructional materials for the week is in the Readings and Resources section. If you want to call special attention to something specific, you can have it here as a separate section. In a typical synchronous delivery modality, your content may be given as an interactive lecture, balancing passive and active learning. HyFlex and Hybrid courses include both online and in-class delivery simultaneously, strategies for content delivery will necessarily incorporate various educational frameworks and technologies. One strategy is taking the Flipped Classroom approach. Do not simply repeat the information students already encountered in the readings and resources. Focus on:

- Expanding their understanding by providing important background information

- Clarifying important concepts by explaining them in a new way

- Connecting new information to previously learned concepts

- Providing real-life examples

- Prompting students to connect content with their lived experiences

Learning Activities/Assignments

This section provides students with opportunities to interact with content, peers, and the instructor. Now that students have worked through the reference and instructional materials, what will they DO? Activities should be relevant, preparing students for success in their evaluated coursework and in their future professions. Activities may be completed by individuals, small groups, or the entire class. They may include personal reflection, class discussion, concept mapping, case study, simulation, educational games, interviews, as well as evaluated course components such as assignments and quizzes.

This section should be used for anything that is graded. The format for assignment activities you choose to implement in your course should be consistent so that students do not get confused. This consistency will allow students to focus on the content and activities rather than the format or the need to search for extra details. For each learning activity/assignment, you will need to provide clear instruction for interactivity, submission, and criteria for assessment. This may be stated in your syllabus, but it is good practice to repeat details here.

See the following example for a discussion activity.

Activity Type (Discussion): (Include a descriptive name for activity)

Use the space to describe activity/assignment. This includes:

- Context for assignment and how assignment relates to reading, other course activities, and/or objective(s).

- Details about how to perform the assignment

- Link or reference to assessment criteria or rubric

- Information about where to submit and if and how to respond to classmates

- When the assignment is due.

Include due dates. for example, for a discussion activity, you will want to provide:

- Post your initial thoughts to the discussion board by day of week at Noon.

- Respond to at least two of your peers by some other day later in the week at Noon.

Provide a rubric or assessment details:

- This activity will be graded out X points, following this breakdown….

Repeat instruction set for as many activities/assignments you plan for the week.

Checklist for the Week

Provide a list summarizing the important due dates for the week. For example,

- Post-initial thoughts to the discussion by Thursday

- Post your field observation to the blog by Thursday

- Post responses to at least two of your colleagues’ discussion posts by Sunday

- Post comments on at least two of your classmates’ blog post by Sunday.

Link to a Word Document with a Module Template Creation Guide.