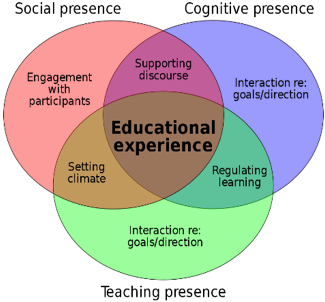

The concept of teaching presence in online course environments originated from the Community of Inquiry framework of online and blended teaching, developed by Randy Garrison, Terry Anderson and Walter Archer from the University of Alberta Canada. They define teaching presence as “the design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes” (Anderson, Rourke, Garrison, & Archer, 2001). While there are many elements supporting teaching presence, faculty are often interested in the impact of instructor-created videos on student learning.

The effectiveness of video in supporting learning depends on a wide range of factors, but some broad guidelines can be helpful. For example, using video for whole-class feedback or guidance created specifically for one particular class or learning activity might be more impactful and less time-consuming to create than pre-scripted, canned videos. You may be curious as to the impact of your recorded visual presence within videos you create. In this video, the presenter reviews some research regarding the impact of having an instructor’s face in the video itself, as well as some general guidelines on the use of video.

In general with regards to instructor-created videos, we advise you to:

- Focus on a specific assignment, on a challenging concept, or for a course or weekly overview

- Use video for feedback or other facilitation

- Use short clips or chunk into short clips (4-5 minutes)

- Choose visuals that support the spoken narrative

- Avoid using a talking head as the only visual

- Do not be overly concerned about verbal mistakes

- If you are creating videos to be used for multiple classes, consider how much time this may take and focus on issues or topics that are durable across longer periods (years) so that you can reuse the resource.

Additional resources on teaching presence:

Role of course design on teaching presence

One instructor’s point of view (research study)

Strategies for teaching presence